Is underground housing a bad thing

What our contributors think

New York’s Housing Underground: 13 Years Later

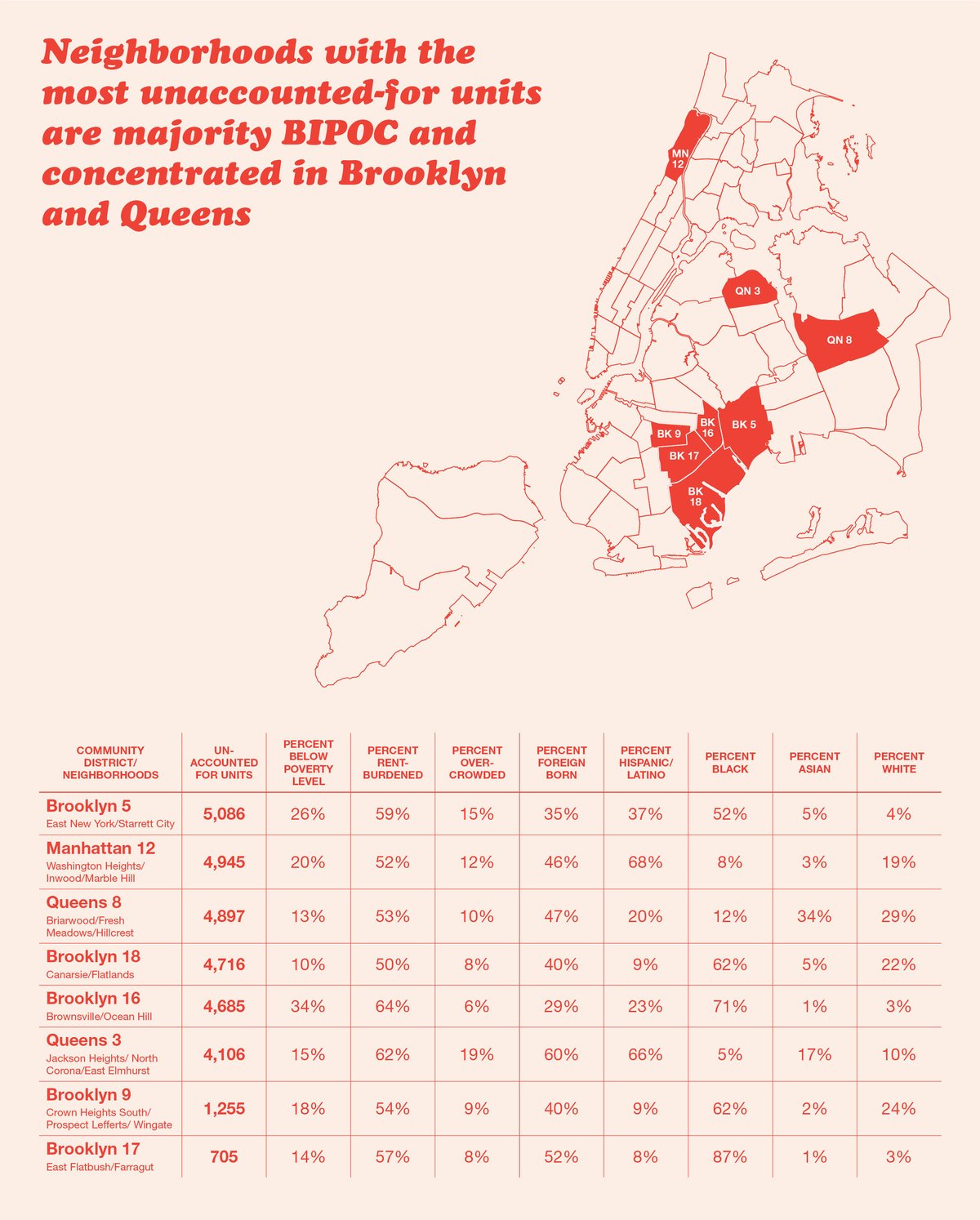

Our 2021 report, New York’s Housing Underground: 13 Years Later analyzed unaccounted for basement and cellar apartments and found that they are predominantly in BIPOC communities with higher levels of rent burden and poverty than the citywide average. This report was an update to our 2008 report, New York’s Housing Underground.”

Findings These unaccounted-for units are largely located within 8 communities:- Brooklyn Community District 5—East New York / Starrett City

- Manhattan Community District 12—Washington Heights / Inwood / Marble Hill

- Queens Community District 8—Briarwood / Fresh Meadows / Hillcrest

- Brooklyn Community District 18—Canarsie / Flatlands

- Brooklyn Community District 16—Brownsville / Ocean Hill

- Queens Community District 3—Jackson Heights / North Corona / East Elmhurst

- Brooklyn Community District 9—Crown Heights South / Prospect Lefferts / Wingate

- Brooklyn Community District 17—East Flatbush / Farragut

Background

Pratt Center undertook this analysis following the devastation wrought by Hurricane Ida on September 1, 2021. Although there has been some movement towards a citywide legalization policy since the 2008 report was published, the avoidable loss of 11 lives in flooded basement apartments during Ida made it clear that there was an urgent need for fresh data that could fuel public conversation and propel action to make these units safe and habitable.

Basement apartments are home to thousands of New Yorkers, many working class immigrants and people of color. New Yorkers living in these spaces are already bearing the brunt of climate disasters, and the City has a responsibility to take immediate measures that ensure habitable and safe homes for all New Yorkers, while addressing the citywide housing affordability crisis. This means decriminalizing basement apartments, updating the building and zoning codes to ease compliance for homeowners while mitigating the threat of flooding, and implementing and providing appropriate funding for programs to upgrade, legalize and regulate basement units.

Is underground housing a bad thing?

The Scottish Rite Masonic temple in Dupont Circle plans to build apartments on some empty space behind its building. One element of the project is two levels of apartments below the ground level. This has raised the question: is underground living an abomination which should be banned because people must have light and air and a view of trees? Or, is this something people can choose to pay (likely less) for, or not, as they wish?

The temple, built in 1915 and designed by architects John Russell Pope and Elliott Woods, is, according to the historic preservation staff report, “based on the Hellenistic temple tomb of King Mausolos at Halicarnassos, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world,” and “among the grandest expressions of the formal classicism that typified the City Beautiful movement in Washington in the early 20th century.” It’s not changing substantially, but it has an open space that’s partly grass, partly parking, in back. Here, the Masons propose to build a new apartment building.

There are three areas of controversy about the project. One is a tax abatement which the local Advisory Neighborhood Commission, DC CFO, and many other people think is unnecessary. This doesn’t sound like a situation deserving a tax abatement, and quotes in a Washington Post article by Paul Schwartzman make it sound like the DC Council is unlikely to move forward with it either.

A second is your more typical neighborhood opposition to new buildings. It will “overwhelm” the nearby townhouses and “block views” of the temple from the back, people say. Our stance on this has long been that DC needs homes for people to live, and that it’s far from uncommon in Dupont Circle (my townhouse is across the alley from an 11-story boxy apartment building which provides homes to many great people).

Anyway, this isn’t a very tall building and I don’t think it overwhelms anything. It probably ought to have some more floors to provide more homes for more people. Schwartzman reports that the temple is avoiding a larger building partly so they can build “matter of right” and avoid zoning changes, which have been the basis for the recent rash of lawsuits. But the temple also rejected an earlier, larger development proposal as they felt it would overshadow the temple itself, Schwartzman reported.

Instead of adding more floors on top, therefore, the plans call for more below-ground units. There will be two “English basement” levels, one just a few feet below ground and the other fully below ground. According to the project documents, both levels will have floor-to-ceiling windows for light. The project team told Schwartzman that they would design attractive patios, perhaps with murals, and ample light.

But some neighborhood activists don’t think living below ground is acceptable at all. When told about the plans for bright lighting, Victor Wexler, a former Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner in the area, rebutted, “What about God’s light?” according to Schwartzman. Edward Hanlon, who was recently elected to the ANC after his expected opponent missed the deadline to file signatures, wrote in an email on the DupontForum list:

Children should not live in and grow up in apartments 15 feet (25 stairs) below ground. Looking out the subterranean apartment window a young child won’t see a tree, won’t see a plant, won’t see a flower, will never see other children playing outside. That child will only see a 17 foot high concrete wall. How can this be good for us as a society or as a neighborhood. Humans were not meant to live at the bottom of trenches. Children were not meant to grow up in “subterranean cellars.”

Another resident replied:

Unless the plan is for children to be held captive in “the cellar” for the entirety of their childhoods, never to be let out to go to school or the library or friends houses or visit a nearby park, [this point] is nothing but … a false narrative to rally the easily frightened.

There were countless apartments in NYC with above-ground fenestration that had (and often still have) no view of streets, trees, or grass, sunlight, or children playing. Just monotonous dingy, soot-covered brick walls, fire escapes, and grimy windows on buildings mere feet away across alleys and breezeways. Generations of kids grew up in them. Countless adults have paid (and continue to pay) good money to live in them. They saw all the things [Hanlon] was falsely claiming they never would see, just not all from their window. My own kids didn’t have all these “criteria” concurrently outside our windows when we lived in NYC. Nor did I growing up in San Francisco.

Here’s a view from Randy Downs, another ANC commissioner in the neighborhood:

What our contributors think

We asked our contributors about this issue. Alex Baca wrote:

I live in a basement apartment. It’s a great apartment, though, to be honest, I would prefer it weren’t a basement. That said, that it is a basement was clearly not enough of a dealbreaker for me not to live there.

So, yes, for the love of God, build apartments below ground.

Some contributors asked questions about safety, Anita Kinney asked, “How does fire egress work for new basement construction in DC?” DW Rowlands added, “Even with extra fireproof stairwells, you don’t get the option of using a hook-and-ladder for a 10-stories-below-ground building like you do with a 10-stories-above-ground one.”

It’s about the building code

Neil Flanagan, an architectural designer, explained how this is an issue for the building code, not zoning:

I want to step back here, to illuminate how an apartment, below-grade or otherwise, is regulated. What can be built is controlled by a very deep and broad set of regulations, not just zoning. This is good because zoning is the least rigorous and empirically based of all of them.

Most of what zoning affects nationally is how far apart things are from each other. How far uses are from each other, how far dwelling units are from each other. Zoning uses these measurements to do most of the work. Other regulations, like rental laws, the building code, and pollution laws more very carefully targeted. Guess which ones actually cut pollution and stop landlord abuse?

In the case of apartment quality, building codes are much more precise, effective, and flexible than most zoning codes. The building code developed specifically out of a life-safety element. It was originally about fire safety, but has grown to encompass sanitation, ventilation, electrical safety, accessibility – and in DC, sustainability features like green roofs.

So what is the public interest here? What is the threat to safety, or health, or even a private cost that should be borne instead of the public, created by below-grade units?

As someone who practices architecture, I have to say the building code show the way. Modern construction means there is no threat to safety, and a pretty marginal level of harm from lack of sun or views of trees. Probably less than looking at your phone in bed or the wine you bought at Cairo Wine and Liquor. Concerns about mold, ventilation, heat, fire safety, and similar issues are very well and rightly addressed in the building code. Let me break a few down.

Modern plumbing and waterproofing basically mean a basement can be as dry as a first floor. Remember, the National Museum of African-American History and Cultureputs almost all of its collection below grade in soaked soils, even though humidity and temperature are some of the biggest concerns to conservators. It is very possible. Flooding is more of a concern on a lower level, but groundwater has to be managed in a building with huge cellar stories and parking grades.

Modern ventilation means even without the windows, a given unit is required to provide enough ventilation and exhaust mechanically. This has become more important as buildings have become more tightly sealed against the environment (see waterproofing above), they can no longer rely on natural infiltration to provide fresh air when windows aren’t open.

As for fire safety, I can’t speak for firefighters, but I can discuss the code approach. The code wants you to take the stairs. Ladder rescue is very dangerous, and don’t forget plenty of buildings are too tall for it. They have to get people out, too. So fire stairs are required with very strict requirements. Additionally, in apartment buildings, the building code requires special “escape and rescue” windows or doors at all levels below the fourth floor, including floors below grade. Finally, the code also requires permanent ladders out of deep window wells where stairs are not provided.

Additionally, all new multifamily residential buildings have sprinklers. Arguably, the cellar units are safer in a fire than most Dupont townhouses.

So what, is left, light? Access to a view or trees? Okay, now we are getting into an argument. Clearly, the units on the north side will get no direct light, and probably not enough reflected light for my tastes. Is it a health problem? Possibly, if you never leave your apartment. It might affect your circadian rhythm or make you depressed. And a lot of light wells are just as bad. If basements are bad, those should go too.

What we know about American zoning is that a lot of the original arguments for it – the concept of “light and air” and fire safety – were effectively pretexts to get legal support for design controls in an era when property rights were sacrosanct. Even to the degree those concerns were genuine, governments had to make other regulations to actually protect the public equitably.

Finally, if the unit is moldy or has an illegally low ceiling, the DC Housing Code will deal with it. At least nominally.

In conclusion, we should be protecting the interests of occupants of units carefully and uniformly – not intervening just because a neighbor thinks something is distasteful.

It’s also worth noting this can provide somewhat lower-cost housing. The developers told Schwartzman that they’d expect these to rent for about 20% less than higher-level apartments. (Some apartments will also be dedicated to below-market renters through DC’s Inclusionary Zoning program, but IZ explicitly specifies that the units have to spread throughout the building, so the IZ units can’t all be in the cellar.)

On the flip side, Dan Reed pointed to this article about a below-ground Manhattan apartment which a couple bought for $1.2 million and then renovated.

But is this ideal?

Not everyone loves the idea of underground apartments. Gordon Chaffin said, “I would live underwater but not underground.” Carolyn Gallaher added,

I have to say that I just find this whole conversation depressing. I want more units built in the city too. But, the fact that we’re scraping for units and are getting excited about 2 nd level cellar units says we have a much bigger problem. There’s just not enough housing in the city. And, I hope this isn’t the way we get there going forward.

Also, this is just me, but living underground would give me the creeps. And, if this is what I’d have to settle for to live in the city (especially if I was a millennial who didn’t have a car and needed to be near public transportation), I’d seriously give those second and third tier cities a look.

I agree with Carolyn that a trend toward below-grade apartments is not /good/, and that we need see this as restrictions on building aboveground pushing things down. The developer wouldn’t consider it otherwise.

Remember, a big reason the building didn’t go up further was because of restrictive zoning and a broken planning process. Neighborhood opponents even now say the building is still too big. Dupont has historic protections which make it hard to build taller. Meanwhile, DC needs housing and Dupont has great transit, bike, and walk access to jobs, and should be a place that welcomes more people.

How would residents most want to do that? Would some tall buildings near Metro be best? More accessory apartments in the rear of townhouses? Convert some row houses to more apartments? Tastefully-designed, minimally-visible pop-ups? Or underground living?

The biggest problem is that there’s opposition to essentially all of these. I think having a neighborhood conversation about the best way to add housing is a good idea. People don’t have to support adding it in every way. They do need to be willing to support adding it in some way. Right now, this is a way that’s legal.

This is a by-right development. … So we’re having all of this discourse and noise and conversation around something that is allowed.

I moved back to DC from a third-tier city this summer. I still own my single-family home there. It’s a beautiful house with skylights in every room. I miss it, and I miss the skylights. Really! But light and air don’t mean much at all when you can’t find meaningful and sustainable employment.

I, too, would prefer our line of argument to be that places where people can live should probably go up rather than down, as a general practice. But I think it’s important to remember that what we’re talking about is something that has already been OKed, functionally. I’m all for healthy discussion … but I want to make sure that in our own conversations we don’t perpetuate the idea that basement apartments are so deeply, discomfitingly abnormal that they should be litigated—especially because a small, vocal, privileged minority is using this project as a proxy to further encode their preferences about what a neighborhood should be.

The preservation board will look at the project Thursday. What do you think?

Continue the conversation about urbanism in the Washington region and support GGWash’s news and advocacy when you join the GGWash Neighborhood!

David Alpert created Greater Greater Washington in 2008 and was its executive director until 2020. He formerly worked in tech and has lived in the Boston, San Francisco Bay, and New York metro areas in addition to Washington, DC. He lives with his wife and two children in Dupont Circle.

Also of Interest

Want a lift? How about three? Metro’s elevators leave some riders behind

Transit Diary: A DC Councilmember shares how he got around during the National Week Without Driving

Transit Diary: A Foggy Bottom resident leans on transit and walking to move herself (and a lot of corn) around town

In our inbox: The costs of bus rapid transit, public financing of stadiums, and Metro under Georgetown

Thanks for reading!

We are reliant on support from readers like you to fund our work. If everyone reading this gave just $5, we could fund the publication for a whole year.

Can you make a one-time or recurring contribution today to keep us going strong?

GGWash is supported by our recurring donors, corporate supporters, and foundations.

All text, and images marked as created by the article’s author, are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.

]]>